Subsidy and Other Preoccupations 13

Yet another letter to the press on the subject of means testing:

By all means, add subsidised beds

Letter from Lan Zhong Zheng

I concur with the opinion of the reader who wrote the letter, "More hospital beds the remedy" (April 26).

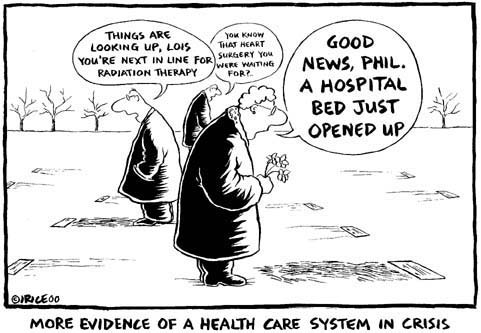

Indeed, from my fleeting hospital attachment at one of the restructured hospitals in Singapore, I managed to catch a glimpse of the crunch faced by government hospitals here.

There was an appalling paucity of available beds in the heavily subsidised wards, while the exact opposite was obvious in the "paying patient" wards.

There were even instances where subsidised patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) were transferred to a Class A ward, just to squeeze out a bed in the ICU for someone whose condition was believed to be more dire and life-threatening.

The ultimate solution is not to carry out means testing on Singaporeans but to increase the supply of beds in the subsidised wards in hospitals here. Implementing means testing infringes on the right of the people to choose.

Does it mean a tycoon should be barred from a superior room and can only stay in a suite? Similarly, why should the middle-income not be given the option of staying in a Class C ward? Being in the middle-income group does not definitely mean one has the money to splurge on a class B1 or A ward.

Looking into supply should be the long-term solution in addressing this shortage. However, as we all know, land is scarce and government hospitals are stretched to their full capacity in terms of facilities and resources.

Rather than diversifying interests by trying to usurp a slice of the burgeoning medical tourism market, the Health Ministry should draw on the HDB model, which sets out to provide public housing to Singaporeans first, especially the less well-off ones. Drawing on this model, healthcare should be focused on catering to the individual needs of Singaporeans, in particular the subsidised pool of patients rather than having to attract foreign wealthy "paying patients" at the same time.

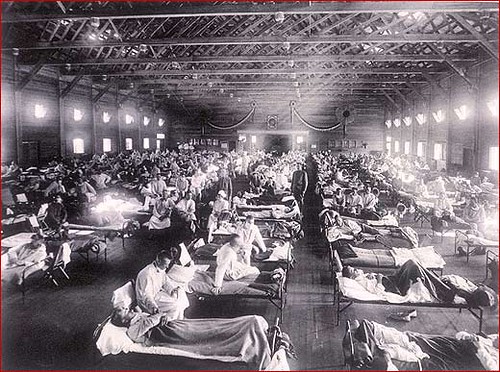

Means testing may bring instant temporal relief to the current situation but with an ageing population and such uncertain times, no one knows when epidemics like Sars will rear its head again. The bed crunch in hospitals may pose a more serious problem then.

Despite our low beds ratio, angry doc is still not convinced that the root problem here is an absolute bed shortage. In fact, the account given in the letter of subsidised patients being lodged in A-class wards tells us that there are beds available in the hospital.

Nor is the problem one of relative bed shortage alone.

In its currently proposed form, means testing does not forbid one from staying in a C-class ward: it merely reduces the percentage of subsidy a patient who fails the means test receives (to less than 80%, but presumably more than 65%). If the patient accepts the lower subsidy, he may still stay in a C-class ward.

So what is the purpose of means testing then?

Is it "to better target our subsidies at those who need them most"?

If so, does that mean that subsidy for those who pass the means test will be increased to more than the current 80%?

Or, is it to achieve "right-siting"?

If so, means testing seems to be too imprecise a tool to achieve that, since it does not take into account whether or not a patient needs to stay in an acute hospital.

angry doc is, once again, confused. Perhaps all the letters to the press published in the past few weeks will prompt a reply from the ministry which will answer all his questions.

Labels: letters, means testing